Frog Forelimb Morphology

What can frog arms tell us about frog evolution?

When most people think of frogs, they often think of their powerful hind limbs and what amazing jumpers they are! And it is true, many frogs are incredible jumpers, but frogs do so much more than that. There are over over 7500 species of frogs after all. There are swimming specialists, climbing specialists, and even burrowing specialists.

What do burrowing frogs look like?

.jpg)

.png)

Notice anything they have in common? You might notice that these frogs look a bit different from frogs most people think about. They have small eyes, large forelimbs, and pointy faces. Their short back legs make for poor jumping performance, but there frogs don’t need to jump when they are digging forward under the ground looking for ants and termites to eat.

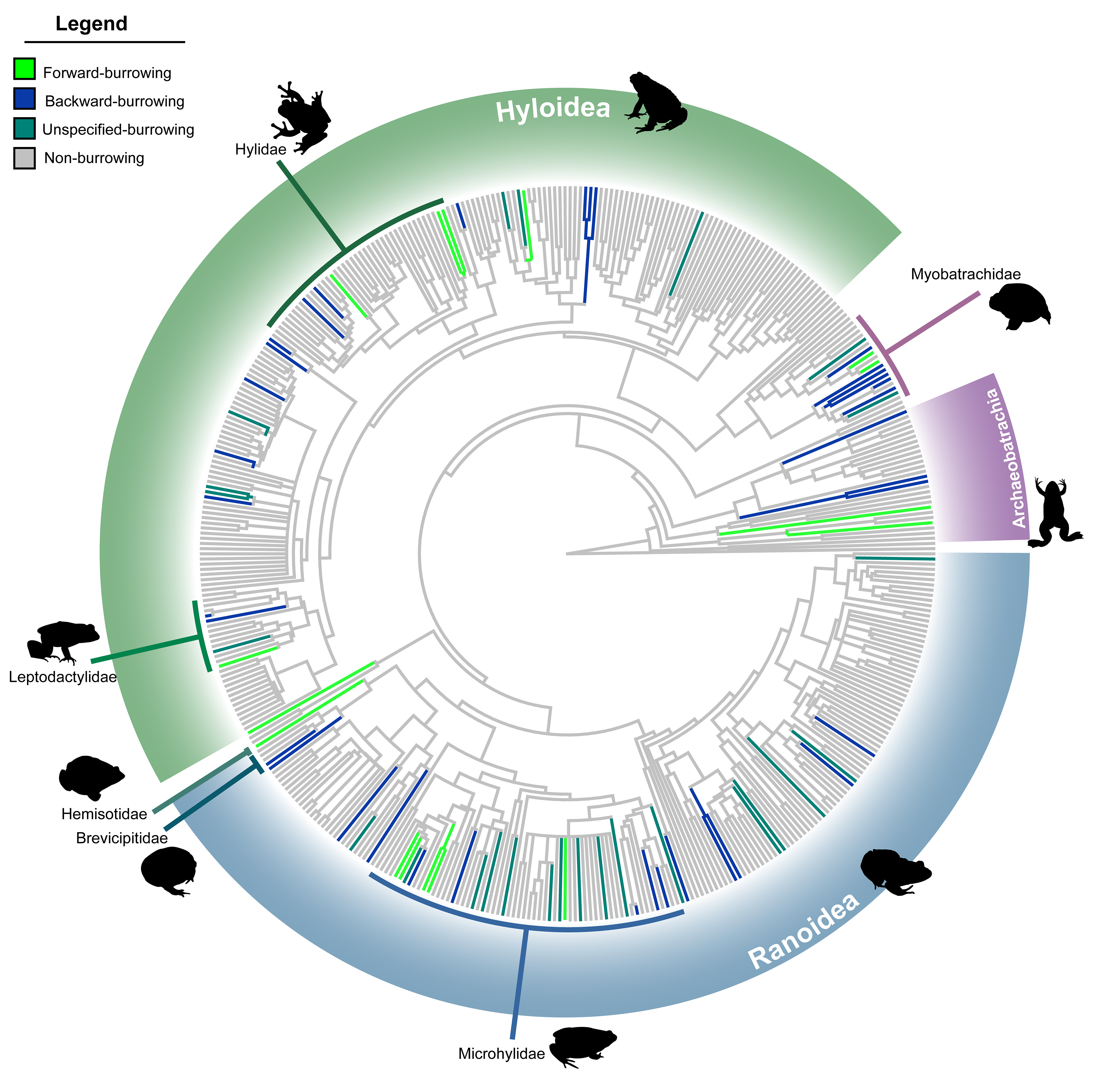

Unfortunately, we still know very little of these burrowing frogs because of their fossorial lifestyle. Until recently, we didn’t know how many times burrowing specialists had evolved in the tree of life. Based on my work from 2020, we know that burrowing has evolved independently at least 8 times across all of living frogs.

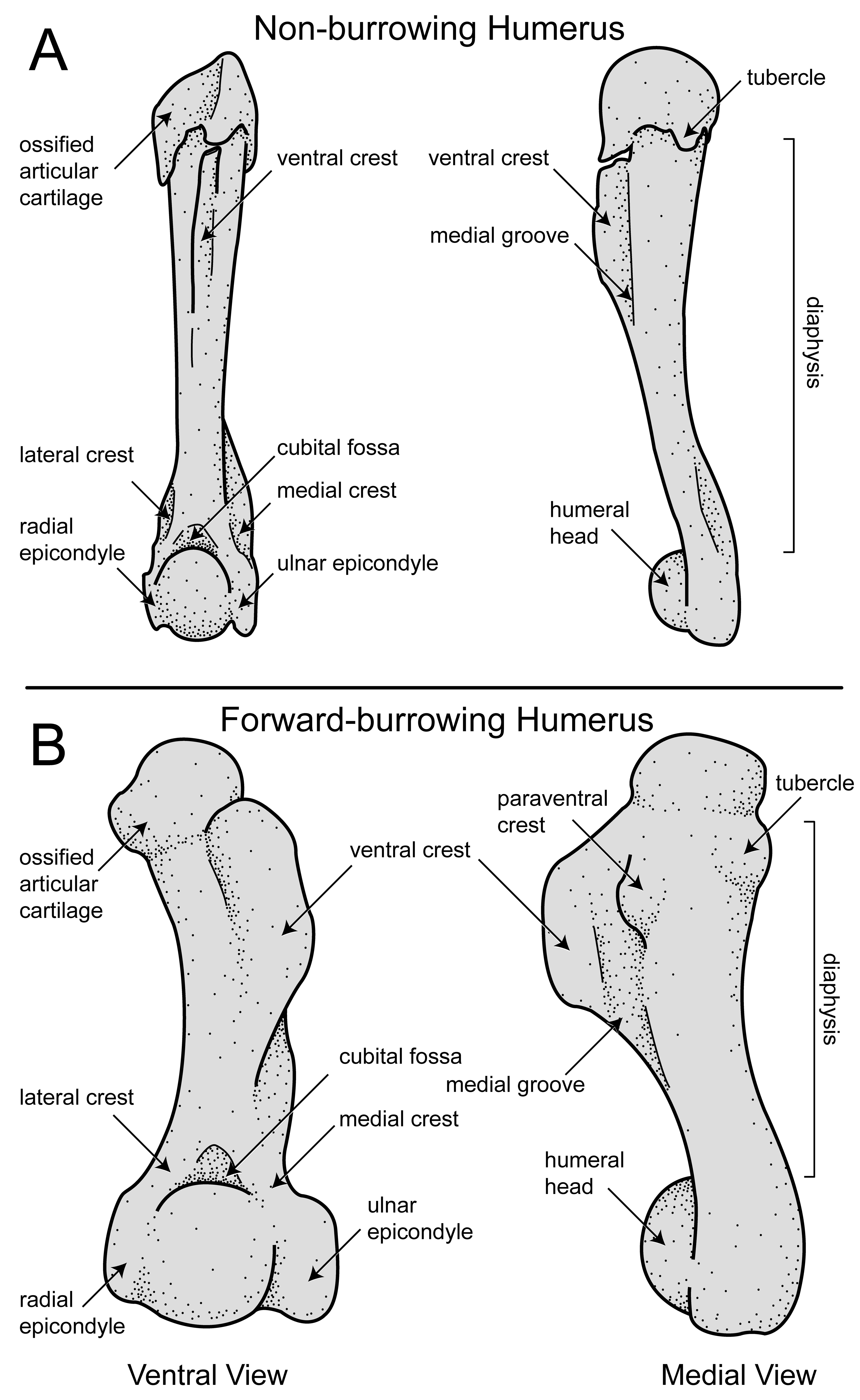

From the same paper, myself and my co-author David C. Blackburn found that the upper arm bone (humerus) of forward-burrowing frogs has a unique shape compared to the humerus of non-forward-burrowing frogs.

As you can see, the humerus of forward-burrowing frogs is relatively thicker than that of a non-burrower. They also tend to have a large ventral crest on the humerus and a relatively large humeral head and epicondyles. All of this allows for greater attachment area on the humerus for the pectoral muscles involved in digging. It also increases the strength of the bone, since it likely needs to resist heavier loads during the digging stroke.

This work is valuable not just for understanding more about the functional morphology of the frog humerus, but also because these results can help diagnose frog species as forward-burrowers based only on their forelimb anatomy. There are many frog species for which little natural history is known, so understanding more about how they locomote in their environment is helpful for helping maintain their habitats. It would also be possible to do the same for extinct species of frogs for which we will never have behavioral data. We hope that this work will prompt further research into the pectoral girdle in all types of frogs, as we know relatively little about it in comparison to the pelvic girdle of frogs, yet it is rich in morphological variation and functional signal.

Co-authors: David C. Blackburn

Funding: The work was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under grant nos DGE-1315138 and DGE-1842473 to R.K. Many of the CT scans used in this study were part of the oVert Thematic Collections Network (NSF DBI-1701714).

Acknowledgements: We thank members of our laboratory group for feedback, analytical advice, and help with segmentation, especially A. Morris, G. Jongsma, D. Paluh and E. Stanley. Three anonymous reviewers also provided helpful comments.